| Art & Technology | |

| - Synaesthesia |

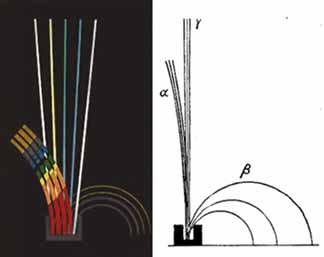

Picabia's work "music is like painting" comes across as a seriously funny take on the European tradition of colour music. Not only is the title an ironic reversal, giving painting precedence over music, but Picabia unashamedly plagiarized a common scientific chart (above, right), showing the effects of a magnetic field on alpha, beta and gamma particles. The result seems to lampoon the pretensions of Enlightenment colour-music codes, and mock their intellectual credibility.

Picabia's

work "music is like painting" comes across as a seriously funny take

on the European tradition of colour music. Not only is the title an ironic reversal,

giving painting precedence over music, but Picabia unashamedly plagiarized a

common scientific chart (above, right), showing the effects of a magnetic field

on alpha, beta and gamma particles. The result seems to lampoon the pretensions

of Enlightenment colour-music codes, and mock their intellectual credibility.

Only when we know the artist counted Busoni, an arranger of Bach's music, among

his composer friends, do we begin to realize that - funnily enough - he might

be serious. Of the many statements the Dadaist painter made connecting colour

with music, none is more cryptic than: "We tend towards the White considered

as a psychic entity or, in order to concretize this tendency thanks to immutable

rapports of colour and music, we tend towards 'la' pure = 435 vibrations." We

are seemingly being told, in the best occult tradition of colour music, that

white and the note A have a physical correspondence and represent, in different

forms, the same mystical goal.

It is

the tempered scale, further rationalized, that we have inherited today. Modern

keyboards, both acoustic and electric, employ a basic method of tuning called

equal temperament, whereby the octave is evenly divided into twelve semitones

by a logarithmic progression. The octave (an interval between two notes of the

same name, created by doubling the frequency of the lower note) is the only

remaining aspect of Western music that might be said to accord with natural

laws. The bottom A on the piano has its frequency doubled seven times over,

producing a cycle of seven octaves, from A to A, before the end of the keyboard

is reached. This man-made construct gives us a mathematical and homogeneous

system for organising sound into music across the audible range.

Music has evolved over millennia, through many compromises,

to a relatively 'impure' state, and its contrived formulae are not echoed in

the natural phenomena of the spectrum. Neither can any unifying principle be

meaningfully divined from the separate vibrations of light and sound: disparities

between them are clear and fundamental. To connect pitch and colour by a relationship

of frequencies would require a formula so convoluted as to be ridiculous - not

that this has stopped many from trying. Helmholtz noted one mid-19th century

example, that raised Pythagorean ratios to the power of six-sevenths in order

to match notes with colours, but rightly pointed out that such a process made

arithmetic nonsense of the original musical proportions.

Helmholtz

realized Newton's alignment of the spectrum to a musical system was physically

preposterous. Still, in the spirit of the times, he toyed with its aesthetic

possibilities; he claimed unnamed Italian painters had preferred his favourite

primaries of red, green and blue and hoped to find musical support for this

thesis. But he had to admit the spectrum of light contains no equivalent of

the basic musical octave, let alone the intervals within it. A comparable light

octave might be envisaged by doubling the lowest red frequency, but doing so

takes one immediately beyond the range of visible light. The spectrum, from

red to violet, can barely span three-quarters of one such 'colour octave', let

alone encompass the cycles of octaves used in music.

Newton's optics went some way to provide a consensual model

of the spectrum, but his colour-music analogy of ROYGBIV was no more than a

pretty conceit. But the search for an overarching unity of colour and music

continued, and even today parallels are being drawn with pure and spectral light.

There are those that still marvel to discover that frequencies of certain notes,

when doubled forty times over, can fall within the measurable range of visible

light. In some quarters, the size of the spectrum has been exaggerated beyond

the range of average vision (personal testimony included as proof), to create

a colour octave. Naive or cynical, such conjuring tricks with dimensions have

taken hold in New Age movements, being used to justify nefarious correspondences

under the venerable name of Helmholtz's pupil, Hertz.

The musical

possibilities of ROYGBIV were explored as early as 1734, with limited success,

by Louis-Bertrand Castel. His ocular harpsichord displayed coloured strips of

paper whenever notes were struck. Castel had at first hailed Newton as his inspiration

(with passing reference to the previous colour music theories of Athanasius

Kircher), and his original colours formed a spectral array. But by 1740, Castel

was using natural colouring materials arranged in a twelve-hued colour circle,

and aligned to a twelve-note chromatic scale cycling over many octaves. Encouraged

by the composer Rameau, Castel embraced a triadic theory of harmony that gave

the primary colours blue, yellow and red the note values C, E and G, making

up the common chord of C major, the white-note scale. The spectral order of

the primaries was reversed to place blue at the bottom, where its expressive

capabilities could best represent the musical ground-base, so important to the

theories of Rameau.

It was not until the end of the 18th century, when subjective

colour effects were attracting scientific attention, that interest in practical

connections between colour and music re-emerged. After repeating Newton's experiments

with colour discs, Count Rumford ruminated on the possibility of:

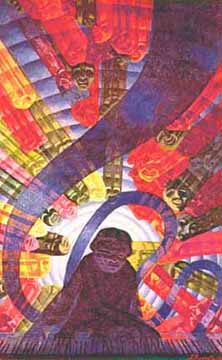

Illustration 10 : "MUSIC." Luigi Russolo, 1911.

Illustration 10 : "MUSIC." Luigi Russolo, 1911.

Though he joined

the Futurists as a militant painter, Russolo soon turned his attention to music.

He created a range of novel instruments, called intonarumori, and published

"The Art of Noises" in 1916. His concerts were attended by the musical and artistic

elite of Europe, as well as the press and rowdy Dada protesters. Russolo's concert

career was curtailed by talking pictures in the 1930s, and he turned to studying

folk music and Eastern mysticism (unlike many other Futurists, he avoided joining

the Fascisti). By trying to break down the distinction between musical sound

and everyday noise, in exploiting the secondary vibrations of his instruments,

Russolo prefigured the concrete music of the 1950s. His legacy remains in computer

music, where his notation system is still used.

Russolo's painting might suggest a belief in correspondences of colour to music.

The clearest clue is provided in a manifesto on "The Painting of Sounds, Noises

and Smells", by his comrade Carlo Carrą: - "...rrrrrrreds that shouuuuuuut,

greeeeeeeeeeeens that screeeeeeam, yellows, as violent as can be." Other Futurists,

the brothers Ginna and Corra, committed themselves to a spectral colour-music

code inspired by their Theosophical beliefs. Bruno Corra's "Abstract Cinema-Chromatic

Music" provides an intriguing account of the techniques the brothers used, employing

the code first on a colour piano then translating the effects to film in 1910-12.

Richard Wagner put out the call for a Gesamtkunstwerk in 1850, a new kind of theatre that would synthesize music, verse and staging into a unified, total artwork. His Beyreuth playhouse introduced the wedge-shaped amphitheatre, hidden orchestra and darkened auditorium, to which audiences are now accustomed. With the introduction of arc lighting (and incandescent globes soon after), theatrical illusion was near complete. Loie Fuller, the Parisian dancer, put these effects to good use, timing her movements in response to atmospheric lighting. Wafting diaphanous veils under ever-changing coloured lights, she inspired Toulouse-Lautrec and D. W. Griffith and influenced Isadora Duncan and Martha Graham. Other were also effected by the Wagnerian spirit. Kandinsky wrote stage pieces from 1909 to exemplify the new values: "The Yellow Sound", "Black and White" and "Violet" , employed the colours themselves, in motion to music, as the central characters. Unfortunately, his works proved too difficult to mount. Around the same time, Schoenberg composed "The Lucky Hand", to be accompanied by a range of colours according to no known theory:

The technical

ingenuity of the late 19th century gave rise to a number of colour music instruments,

like Rimington's or Bainbridge Bishop's (the latter being displayed by P. T.

Barnum). Typically, they took the form of a standard organ console with a screen

above it, onto which different colours were projected - usually a standard spectrum

was divided into a progression to match the C scale. Colour musicians often

justified their work with references to science, spirituality and the grand

order of nature, while the press shared their enthusiasm for a potentially revolutionary

new art form. The musical component of colour music was frequently eclipsed

by the novelty of colour music instruments. Thomas Wilfred, sponsored by prominent

Theosophists, had devised large spectacles in New York in 1916; he later invented

the Clavilux, his light organ, to perform Lumia concerts. By 1930, he had put

the Home Clavilux on the market. Before the advent of television, a buyer could

install a cabinet in the corner of the living room that silently generated visual

imagery for days - without producing the same pattern twice.

After World War I, some film-makers had turned their attention

to colour music as an ideal subject for abstract animations. Sometimes, they

might collaborate with an artist (Viking Eggerling with Hans Richter) or work

with a colour organist (Oskar Fischinger with Alexander Laszlo). Their valuable

innovations were often obscured by later advances in mainstream film - the advent

of talkies and colour films - and public attention diverted to bowdlerized versions

of colour music, such as Disney's "Fantasia".

Not until the rock shows of the 1960s and 70s did colour music

regain a large audience, with psychedelic performances synthesizing light and

sound. Pioneering work in electronics and computing enabled animators to participate

in major films as well - John Whitney's contribution to the Stargate Corridor

sequence in "2001: A Space Odyssey" being one example. The effort to co-ordinate

colour and music on domestic computers has led to further software advances.

In exploring possible interrelationship of colour and music, programmers have

been obliged to analyse anew the formal elements, to map flexible links between

any arrangements of pitch, colour, shape, movement and so on. Video makers and

live performers have been able to take advantage of the broad theories supplied

by traditional colour music. Even something of its persistent mysticism has

been readily assimilated in the age of multimedia. Modern computing and animation

experts can (and often do) claim a lineage that extends back through colour

organists and animators of the early 20th century, to Castel's Ocular Harpsichord

in the 18th century - even unto Athanasius Kircher's magic lanterns and Arca

Musarithmica (mechanically-composed music) of 1600.