| Art & Technology | |

| - Synaesthesia |

In 1919, one of Australia's most controversial art exhibitions was held in Sydney. Called "Colour in Art", it attracted a crowd of 700 to the opening, an occasion of fervent debates by all accounts. The cause of the furore was the artists' use of colour. One of the two exhibitors, The other was Roy De Maistre, a young musician-turned-painter, whose musical training was evident in the titles of many paintings on display. "Still-Life Study in Blue-Violet Minor" was typical: while the subject was realistic the colours were chosen to harmonise like the notes in music. Blue-violet was supposed to be F sharp, so this painting was designed in colours aligned to the key of F sharp minor. Hung at the back of the exhibition were De Maistre's colour charts, showing how specific musical notes corresponded to different hues to form a colour-music code. After De Maistre's death in 1968, the charts found their way to the Art Gallery of NSW, and so colour music gained a permanent place in Australian art history. Their importance had been guaranteed when, in 1959, the large painting "Rhythmic Composition in Yellow-Green Minor" surfaced at auction. Dated 1919, it was hailed as the first example of Australian abstraction, composed by De Maistre on colour-music principles. The recent release of Heather Johnson's "Roy De Maistre: The English Years, 1930 to 1968" throws fresh light on later work. Like the first volume of his biography, "Roy De Maistre: The Australian Years, 1894 to 1930", it emphasises the continued importance of colour music to this artist.

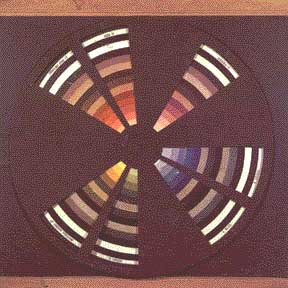

The colour music principles used by De Maistre in his paintings formed the basis

for this commercial device, sold to interior decorators and students as a guide

to colour harmony. The dark, outer mask could be rotated to reveal different

colour combinations on the chart beneath. The holes in the above example are

spaced in accord with the intervals of a harmonic minor scale (there was a corresponding

mask for the major scale, with differently-spaced holes). The keynote is at

the bottom left, positioned in this case over D and green, to give an overall

key of D minor (or green minor) when read in an anti-clockwise direction.

De Maistre's

colour chart took the form of a wheel. A flow of colour, like a rainbow, formed

the rim. Spokes divided the wheel into twelve segments with different colours

and notes allocated to each segment. The relationship between colours and notes

followed a simple order: the seven white notes of the keyboard (A, B, C, D,

E, F and G) were given to the seven rainbow colours of red, orange, yellow,

green, blue, indigo and violet (or ROYGBIV for short), and in that order. This

made up a colour-music code, starting with red-equals-A at the bottom end. Musical

pitch then increased note by note up the scale, paralleled by a similar movement

of colour through the spectrum, ended with violet-equals-G. Scientifically,

this created a sequence in which the frequencies, or vibrational rates, of both

light and sound progressively increased.

The ROYGBIV

colour sequence had long been used as a shorthand expression for the colours

of the rainbow. It was devised by Sir Isaac Newton to describe the artificial

spectrum he first produced in 1666. When he split sunlight with a prism, Newton

produced a continuum of pure colours - the spectrum. He initially noted eleven

basic colours, later reducing his description to five broad hues. For the publication

of "Opticks" in 1704, orange and indigo were added to create the seven-hued

rainbow, ROYGBIV, that is commonplace today. This structure was an artifice,

designed by Newton as a metaphor for certain traditional musical scales. The

chord of the basic key was represented by the triad of primary colours, red,

yellow and blue. Adjacent colours were held not to agree and intervals of fifths

(such as red and blue) were considered harmonious, as in music. And so a crude

colour-music code was created.

Using the same colours, De Maistre constructed his own code,

aligned to the white notes of a modern keyboard. He began at the beginning,

with red and A, the first-named note. A is also the first note in the bass of

the piano, and during De Maistre's lifetime A emerged as the international standard

of pitch, at A440 cycles per second. Its musical primacy could not be ignored,

so De Maistre assigned A to red, the first colour visible at the low end of

the spectrum. Both Heather Johnson and the art historian Mary Eagle have written

that De Maistre's code commenced at middle C and yellow, the middle of the spectrum.

While yellow may stand out amongst the colours as a logical starting-point,

this is due to its intensity rather than it being in the middle of the spectrum

- a position in fact occupied by green. Indeed, yellow was aligned to C in De

Maistre's code and the white notes, assigned to the other spectral colours,

made up the key of C major. But equally well, the same notes make up the key

of A natural minor; this has the same key signature as its relative major C,

both showing no sharps or flats. The alignment of C with yellow was coincidental:

De Maistre's musical knowledge obliged him to begin his colour-music code with

A, at red. Other less sophisticated colour-music codes have used C as a starting

point, but invariably assign it to red, not yellow. At the low threshold of

vision, red is the logical beginning for sequences of spectral colour.

Having

formulated the basis of his code, De Maistre then had to join the opposite ends

of the spectrum together, to make the rim of his colour wheel. A non-spectral

colour was added, blending the red and the violet of the spectrum's ends. This

'impure' red-violet was given the musical note of G sharp, half-way between

the notes of A (red) and G (violet), so connecting the ends of the white-note

scale. The black note, G sharp, is often added to the key of A natural minor

as an accidental, individually marked each time it appears but not present in

the overall key signature. A heightened musical effect is achieved by raising

G to G sharp, immediately before the climactic keynote of A, and the formal

consequence is a change of key to A harmonic minor - the type of minor key that

predominated in De Maistre's time, as it has for the last two hundred years.

The basic wheel was formed by the addition of an 'impure'

red-violet and the 'accidental' G sharp in the twelfth segment. De Maistre's

next task was to insert the remaining four black notes - C sharp, for example,

was placed in a segment of yellow-green colour, between C at yellow and D at

green. In this way, a graduated colour wheel was built up to represented the

twelve notes of music, and De Maistre's colour-music code was formed. Travelling

round and round the wheel mimicked the cycle of musical octaves (from A to A

and so on up the scale), all the while accompanied by a smooth flow of changing

colour.

Division of the spectrum into eleven sections provides a check on De Maistre's

code. In a best-fit situation, most notes and colours match up as they should.

The chief discrepancy is at the top end, where G does not coincide with the

violet De Maistre allotted to it, but has to be moved into the extra twelfth

segment, outside the spectrum. This is an 'impure' red-violet, originally set

aside for G sharp, which in turn must move to deep red.

De Maistre's

colour-music code had a formal niceness, a serendipity to it, that other codes

would be hard-pressed to match. But in any application to painting, the code

presented practical problems that were difficult to overcome. The red-violet-blue

section of his colour wheel took up six segments, or half the colour range.

Three or four of these colours would automatically be included among the seven

notes of any scale, giving his colour schemes a violet slant. Mary Eagle noted

that De Maistre's palette tended towards violet in his early work. This may

not be, as she supposed, just the result of a personal taste but rather an inevitable

outcome of the colour-music code he used.

Particular difficulties would have arisen in differentiating

between overall major and minor schemes. The semitone differences between the

third and the sixth notes of the major and minor scales could result only in

slight shifts of hue, involving but two of the seven colours. This would seem

insufficient change to express the radical difference in musical mood, between

positive major and mournful minor.

One could suppose that De Maistre, in his early works at least,

chose a palette from the colour wheel according to a predetermined major or

minor key; this was then employed on conventional subjects, modifying the local

colours of still-lifes or landscapes, such as "Boat Sheds, Berry's Bay" (1919).

Great scope for interpretation was available with such a wide range of colours,

but artistic licence was limited by the need to balance the differing requirements

of the colour-music code, recognisable local colour and pictorial composition.

Ambiguities

are present in any code attempting to translate music into colour. For instance,

red might stand for the note A but this does not tell us which one of them,

high or low: red might just as easily represent the scale, the key or the chord,

all based on A. Such technicalities became important in De Maistre's later paintings,

such as " Arrested Phrase from a Haydn Trio in Orange-Red Minor " (1935). Here,

he turned to the task of transcribing music, for which his colour-music code

seemed purpose-built. Fragments of music were painted as flat patterns of colour,

moving from left to right as if the music manuscript had been encrypted in the

colour-music code. Some tonal variety was introduced, along with some enigmatic

graphic elements; with tightly controlled means, De Maistre created fairly complex

designs to express only small amounts of music.

Later work suggested De Maistre was emphasizing a chord-based,

rather than a note-based, application of his colour-music code. The august Romantic

music he interpreted gave common combinations of chords, based on the first,

fourth and fifth notes of the scale. When translated via the colour wheel, these

yielded abrupt colour contrasts - a red key (A) would be augmented by green

(D) and blue (E) chords. (These are the main colours present in the Haydn piece

mentioned above. It is hard to see the orange-red, blue-green and indigo that

one would expect from the title, suggesting the piece may be misnamed.) With

few chords based on other notes - especially in a short fragment - the music

lent De Maistre's mature paintings an inevitably brazen, heraldic colouration.

And underlying all the details of De Maistre's scheme was a quasi-scientific

assumption, common to most colour-music codes - that a mathematical relationship

of frequencies, or vibrations, united the physical phenomena of light and sound.

A similar concern preoccupied many artists overseas and news might have filtered through to the Australians of parallel developments in the field of colour music. When De Maistre attended recitals on the colour organ, by Alexander Hector in 1918, he may have been aware that the synaesthete, Alexander Scriabin, had scored "Prometheus: a Poem of Fire" to include a colour organ, in 1915. In both cases, arcs and waves of colour were projected onto overhead screens, in time to the music. Painters, too, were transferring musical ideas to canvas - Kupka, Van Doesburg, Russolo and the Delauneys on the Continent, and Klein, Rimington and Duncan Grant in England, had all treated musical subjects prior to the end of the First War. De Maistre could have been up with these developments: through Wakelin, he seemed to particularly absorb the influence of the Synchromists Russell and Wright, who worked at colour music in America. Because of, or apart from these influences, a brief moment in Australian art history emerged when colour music took centre stage, with Roy De Maistre as its chief exponent.